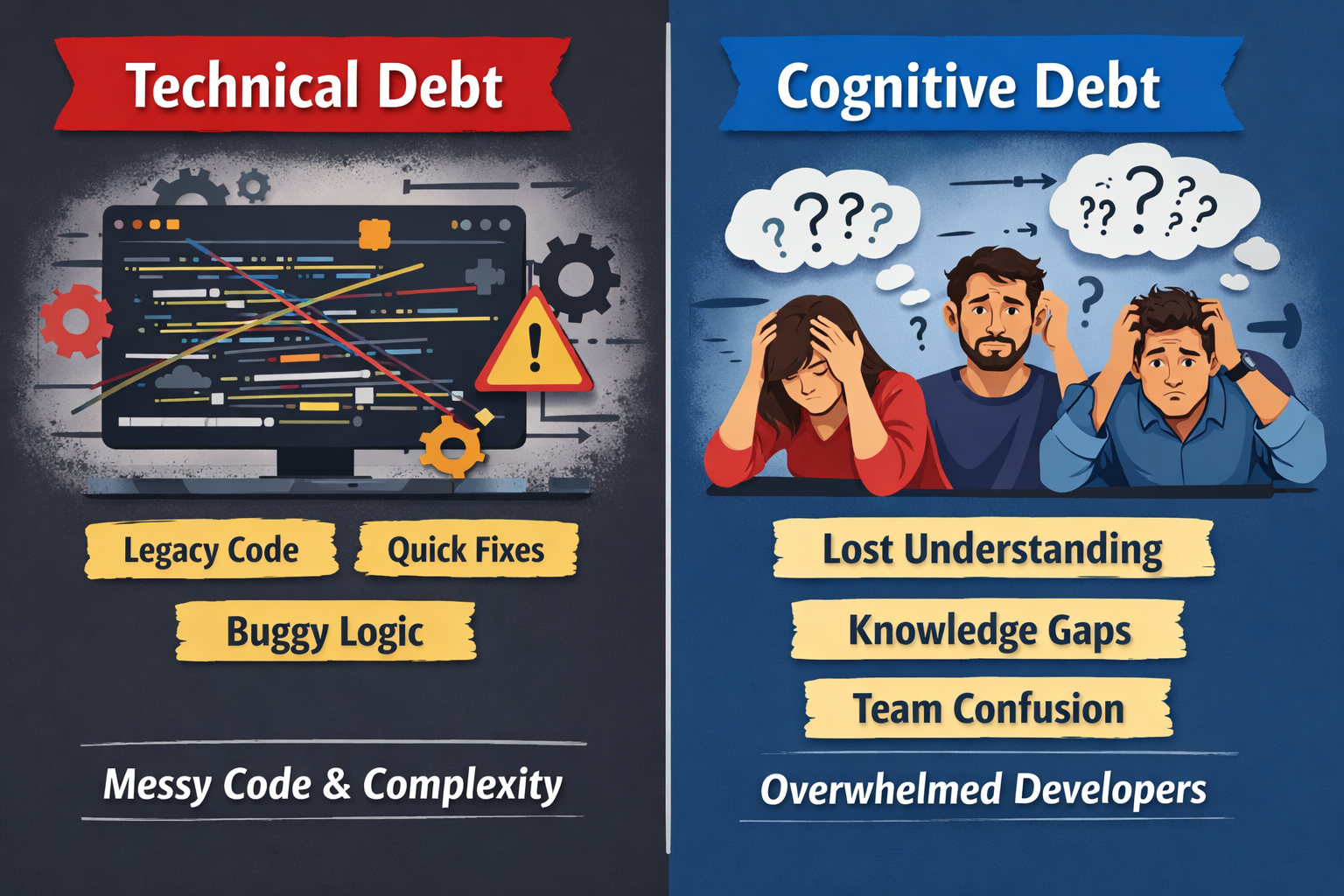

The term technical debt is often used to refer to the accumulation of design or implementation choices that later make the software harder and more costly to understand, modify, or extend over time. Technical debt nicely captures that “human understanding” also matters, but the words “technical debt” conjure up the notion that the accrued debt is a property of the code and effort needs to be spent on removing that debt from code.

Cognitive debt, a term gaining traction recently, instead communicates the notion that the debt compounded from going fast lives in the brains of the developers and affects their lived experiences and abilities to “go fast” or to make changes. Even if AI agents produce code that could be easy to understand, the humans involved may have simply lost the plot and may not understand what the program is supposed to do, how their intentions were implemented, or how to possibly change it.

Cognitive debt is likely a much bigger threat than technical debt, as AI and agents are adopted. Peter Naur reminded us some decades ago that a program is more than its source code. Rather a program is a theory that lives in the minds of the developer(s) capturing what the program does, how developer intentions are implemented, and how the program can be changed over time. Usually this theory is not just in the minds of one developer but fragments of this theory are distributed across the minds of many, if not thousands, of other developers.

I saw this dynamic play out vividly in an entrepreneurship course I taught recently. Student teams were building software products over the semester, moving quickly to ship features and meet milestones. But by weeks 7 or 8, one team hit a wall. They could no longer make even simple changes without breaking something unexpected. When I met with them, the team initially blamed technical debt: messy code, poor architecture, hurried implementations. But as we dug deeper, the real problem emerged: no one on the team could explain why certain design decisions had been made or how different parts of the system were supposed to work together. The code might have been messy, but the bigger issue was that the theory of the system, their shared understanding, had fragmented or disappeared entirely. They had accumulated cognitive debt faster than technical debt, and it paralyzed them.

This dynamic echoes a classic lesson from Fred Brooks’ Mythical Man-Month. Adding more agents to a project may add more coordination overhead, invisible decisions, and thus cognitive load. Of course, agents can also be used to manage cognitive load by summarizing what changes have been made and how, but the core constraints of human memory and working capacity will be stretched with the push for speed at all costs. The reluctance to slow down and to do the work that Kent Beck calls “make the hard change easy” is what will lead to cognitive debt and load in the future.

In a breakout session at a recent Future of Software Engineering Retreat (arranged by Martin Fowler and Thoughtworks) we discussed how developers need to slow down and use practices such as pair programming, refactoring, and test-driven development to address technical debt AND cognitive debt. By slowing down and following these practices, cognitive debt can also be reduced and shared understanding across developers and teams rebuilt.

But what can teams do concretely as AI and agents become more prevalent? First, they may need to recognize that velocity without understanding is not sustainable. Teams should establish cognitive debt mitigation strategies. For example, they may wish to require that at least one human on the team fully understands each AI-generated change before it ships, document not just what changed but why, and create regular checkpoints where the team rebuilds shared understanding through code reviews, retrospectives, or knowledge-sharing sessions.

Second, we need better ways to detect cognitive debt before it becomes crippling. Warning signs include: team members hesitating to make changes for fear of unintended consequences, increased reliance on “tribal knowledge” held by just one or two people, or a growing sense that the system is becoming a black box. These may be signals that the shared theory is eroding.

Finally, this phenomenon demands serious research attention. How do we measure cognitive debt? What practices are most effective at preventing or reducing it in AI-augmented development environments? How does cognitive debt scale across distributed teams or open-source projects where the “theory” must be reconstructed by newcomers? As generative and agentic AI reshape how software is built, understanding and managing cognitive debt may be one of the most important challenges our field faces.

I’ll be exploring these questions further in a keynote at the ICSE Technical Debt Conference and Panel. Cognitive debt tends not to announce itself through failing builds or subtle bugs after deployment, but rather shows up through a silent loss of shared theory. As generative and agentic AI accelerate development, protecting that shared theory of what the software does and how it can change may matter more for long-term software health than any single metric of speed or output.